Liverpool

By Lisa

PCUK’S LIVERPOOL WALKABOUT was packed with living history, ambition, ‘sticky streets’, best practice and regrets, plus loads of inspiring people and projects. The visit was organised by PCUK co-founder and ShedKM Managing Director Hazel Rounding, who’s worked extensively in the city. Roughly half of the group hailed from or now work in Liverpool and all shared interesting stories.

Much of the trouble the city is recovering from stemmed from a 1990s decline that hollowed the city economically and physically, resulting among other things in an anomalous chunk of low-density housing near the waterfront.

European Union funding and the 2008 European Capital of Culture designation started to turn things around, with mixed results. There was a marked improvement in local pride and outside media coverage. Looser licensing meant a stronger drinking and clubbing culture, mixing night-time revenue and cultural vitality with ‘sticky streets’. Architectural heritage was celebrated, from imposing St. George’s Hall to tucked-away Bridewell prison-turned-pub. So was new big-footprint retail, leisure and tourism in the city centre and on the docks.

More recently, Liverpool lost its UNESCO World Heritage status due to waterfront development including Everton stadium. The timing and reasoning are ironic, since the city, and especially National Museums Liverpool, is opening some of the darkest chapters of its international history, recognising its leading role in slavery and offering a more honest view of Liverpool’s maritime heyday and a more inclusive present-day programme.

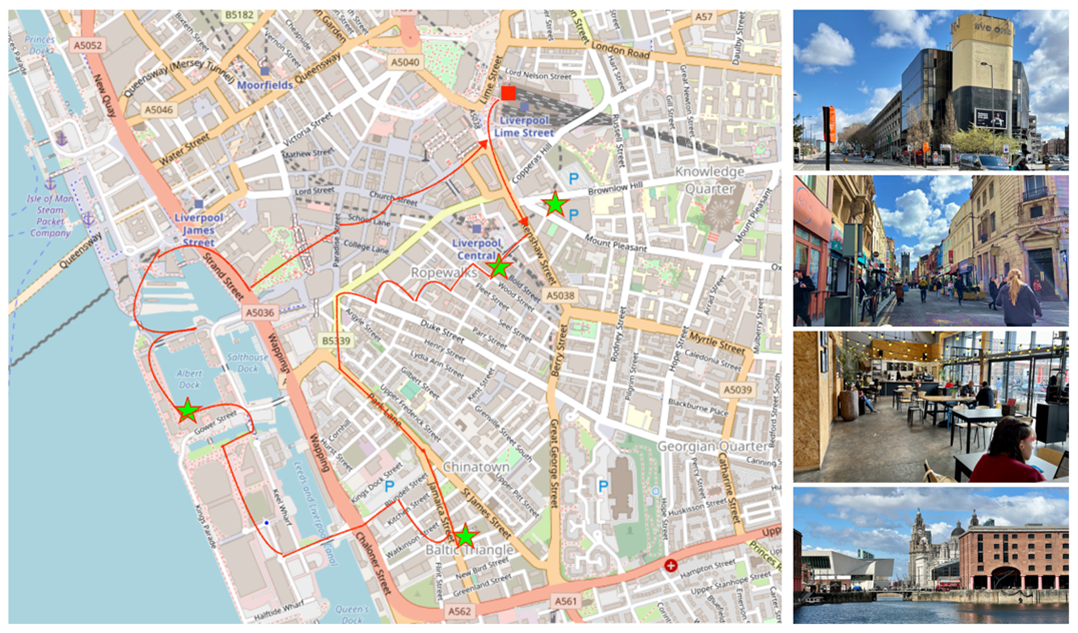

FROM THE VAST, GREY Lime Street Station forecourt, we passed historic Grand Central Hall and the highly Instagrammable ‘051’, a former club derelict since 2016. Its shell attracts crime but hasn’t been redeveloped; the prime location also includes some of the only council-owned parking in the centre. A second fire in August 2022 may speed change.

Lots of the architecture in the centre is interesting, from industrial brawn through ‘50s sleek, and the ground floor offer is starting to match, as part of Liverpool’s gradual recovery. Ropewalks has evolved over the last 10 years, especially the Bold Street pedestrian area and refurbished warehouses on Seel and other streets. It feels egalitarian, with a burgeoning café culture, trendy workspace and independent shops cheek-by-jowl with pubs, clubs and eateries. Urban interventions like Concert Square, new through-routes and public art link these worlds.

AS WITH MOST CITIES, Liverpool’s vital spaces spread from nodes – Ropewalks, the Georgian Quarter, the Baltic Triangle, the Knowledge Quarter, Albert Docks and more – with dead zones between, like behind Liverpool One, where back-of-house retail and bland student housing and hotels overshadow protected pubs. Elsewhere, ‘tinned up’ shopfronts show we’re still far from economic recovery.

IN THE BALTIC TRIANGLE, one group has been helping small businesses thrive despite outside forces. Baltic Creative CIC was established by a group of locals, including visit host Miles Falkingham, who asked: “what if the creative and digital sector owned the property it was regenerating? So instead of being nudged out as values rose, the sector benefited and was able to reinvest in itself?”

With a £4.5m grant and a lot of effort, they transformed 18 warehouses in the Triangle, home to industrial and commercial occupiers for decades. It’s important to the Community Interest Company that these businesses – car repair, food prep, textiles, etc – can afford to stay and feel part of a neighbourhood that now includes digital and creative outfits and buzzy culture and hospitality spaces.

The Baltic Creative main building offers a café and workspaces in garden sheds (or parts thereof) arrayed along streets inside a giant industrial shed. The focus is on digital industries, said Operations Manager Chris Greene, and with at least one inquiry a day, the place is always full. The CIC needs a reasonable yield, but rates are manageable, and the tenant churn is healthy.

SO IS THE MODEL. Greene said occupiers stay for at least a year, pay business rates and were eligible for Covid grants. Owning the building is critical, and the CIC has a 250-year lease. Surplus is reinvested and the company can hold debt and lend against assets.

The CIC team is happy to see imitators, provided they “don’t chase the money so hard the character gets lost”. A recent area addition is the 30,000sqft Camp and Furnace complex, where affordable workspace is part-funded by events, exhibitions, food pop-ups and a café.

Now the CIC is exploring the idea of affordable housing as part of the local mix. Whether they develop it, manage it and/or partner with a housing association are open questions, and fodder for an ongoing conversation with London-based Bow Arts, which operates on a similar model and had two reps in our group.

“MAKING SOME NOISE” is key to Baltic Creative’s strategy – hosting visits, publicising wins and working with partners. That tactic has also been working at Albert Docks, home to the first regional Tate museum and much of the 21-building National Museums Liverpool (NML) complex.

After making it across King’s Dock, with its stadium, carparks, hotels and acres of windswept ‘crowd management’ space, we met NML dynamo Mairi Johnson, Director of Major Projects. She outlined the museum’s growing focus on the slavery aspects of Liverpool’s maritime story and on celebrating a much broader range of history and culture.

She also shared a straightforward approach to getting things done despite Covid, economic and government challenges: Plan well, stay flexible, and “go with what’s happening” to snag any funding or policy luck that comes along. She said NML’s “superhero” team does a lot, with galleries, school outreach, online presence, events, filming and more. Now it’s time to make the museum’s extensive land, drydock and building assets deliver more.

THE MONEY to do that includes £20m of Levelling Up funds, split with the Tate Liverpool. The catch? They must spend it in two years, so there’s a lot of emphasis is on visible small-project results and procuring at pace for the bigger projects. With planning work underway and the Tate already naming its architect, they’re well on the way!

There are useful lessons here for place-based work. The museum makes sure the whole team, including back-office, understands and engages with the public offer. They’re also using this tight timetable to “develop as a client” and to work on strategy and partnerships. One partner is Birkenhead, across the river, where a £2m Town Fund grant will support a new highline park linked to the NML Transport Museum.

WE ENDED with a view of the possible future from Rounding and Plan-It IE Studio Director Anna Couch, who used RIBA’s stylish Liverpool HQ to share a vision for the Ten Streets neighbourhood, a provocative Strategic Regeneration Framework for Mathew Street and other exciting possibilities for people and place (links below). Part of the ethos both shared was a shift from formal planning tools toward local autonomy, and from defensive, reductive, or reactive planning to more expansive methods. We certainly saw lots of the latter on this visit and hope it continues to build momentum.

Thanks to everyone who hosted us and share insights, including our Liverpool-based participants!

Links from PCUK host Hazel Rounding

https://www.visitliverpool.com/blog/read/2020/02/neighbourhood-ropewalks-b383

https://www.baltic-creative.com

https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/waterfront-transformation-project

https://www.liverpoolbidcompany.com/commercial-district-bid/

https://www.planit-ie.com/reimagining-world-famous-mathew-street/

https://www.tenstreetsliverpool.co.uk

Academic critique of European City of Culture Legacy: tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09654313.2021.1959725